The Sheepskin Email

Posted: February 18th, 2024 | Author: Matt | Filed under: DFW, Uncategorized | Tags: DFW, DFW Conference, email | No Comments »This is a little something I wrote a long time ago, for the first DFW Conference at Illinois State University, in 2014.

I remember submitting a proposal to that conference and wanting to do something short and easy but also something that relied on Wallace’s archive at the Ransom Center. I think the only place it was published before was in the volume of conference papers.

The Sheepskin Email by Matt Bucher

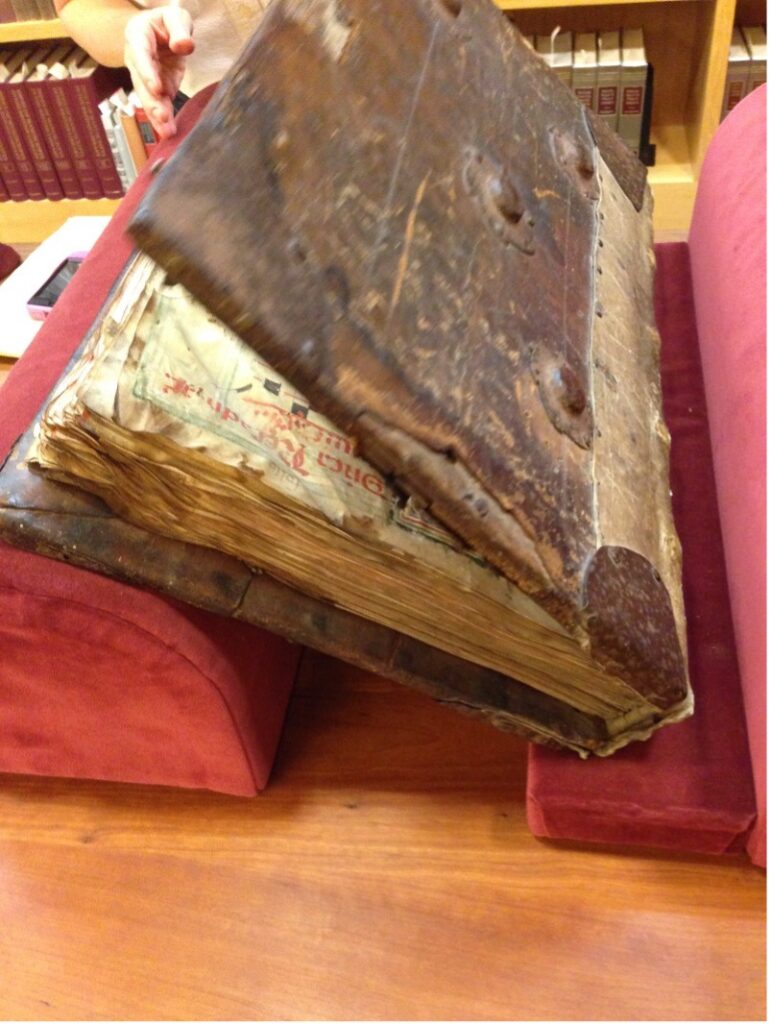

One day I was sitting in the well-appointed and hallowed space of the central reading room at the University of Texas’s Harry Ransom Center, and at my large oak table, I was gently handling a manila folder with plain white sheets of printed-out emails. I was carefully turning through 8.5” x 11″ xeroxes of emails written by turdnagel@comcast.net when I noticed two librarians approaching me, wheeling a massive cart. Apparently the woman at the table across from me had requested a four-foot high, leather and sheepskin-bound Latin processional book published in Spain in 1462. It came wrapped in a custom velour blanket, and was transported in its own cart. It required two librarians to lift the heavy object from the cart onto the table’s special pillowed, bookstand, the way two paramedics might lift a dead body off a gurney. As I watched this ceremonial procedure take place, I wondered if I was not watching a brief morality play about the progress of technology. It was as if the future of literary archives had set these two endpoints before me, leather and sheepskin at one end and email at the other.

And yet, even as an object, that turdnagel email address interested me more than the Latin processional tome. I had gone out of my way to read these emails (on paper) because they make up part of the officially archived correspondence of David Foster Wallace. And I was curious about how a writer born on one side of the digital divide interacted with technology over the course of his career. The way he chose to communicate matters, I think. Do many writers working today bother to preserve their emails or digital files for archivists?

David Foster Wallace began his writing career in the analog era—and he remained distanced, skeptical, and downright resistant to computers, email, and the Internet in general, but he did use them eventually.

Some of the purest evidence of Wallace’s life in the analog era comes in the form of the handwritten drafts of Infinite Jest available in the Ransom Center. The drafts are extensively worked over, with annotations and edits, often in different colors of ink. The pen is clearly an extension of the author here. This makes the editing and creation process transparent. And yet here is little-to-no evidence of how his edits worked on his own Word documents. The archives include no printouts of PDF markup tools or Word’s track-changes function. How did the computer, the machine influence his creative process? It’s an interesting question, but today I want to focus on his correspondence.

Wallace’s first manuscripts written on a computer came in the early 1990s, but it was not until 2001 in Illinois that Wallace began using email, though he had certainly tried out the World Wide Web before then. The process that initiated his adoption of email was his need to communicate with his agent, who was in California, his publishers in New York, his research assistant (on Everything & More) in Bloomington, and his family and friends. Up until 2001, DFW had communicated with his agents exclusively through phone calls and mailed letters (and occasional in-person meetings).

By 1994, most college campuses had system-wide email, but it was relatively easy for the stubborn professor or two to shrug it off—at least until the turn of the century or so. In “Tense Present,” published in 2001, he wrote “You don’t, after all (despite withering cultural pressure), have to use a computer.” Any professor shunning email or computers entirely these days is the stuff of legend.

In 1988, Wallace told Steven Moore, “I’m shitty at computers.” His initial forays into electronic publishing and word processors made him feel old. Although he eschewed fancy pens and bonded paper, he preferred the comforts of a simple Bic pen and legal pad. Computers, and technology in general, were a cause of frustration in his life and work.

In late 1999, Wallace accepted an assignment from Rolling Stone magazine to cover the McCain campaign and the 2000 presidential primary in South Carolina. His turnaround time from traveling with the campaign to submitting his piece was incredibly tight: he had fewer than three weeks to write and edit the piece. The leisurely editing pace Wallace experienced with longer lead-time publications was gone and he had to do most of the editing over the phone or, shudder, by driving across town to a Kinko’s to fax in revisions.

This brutal experience informed his decision to perhaps give email a try once he began the process of writing and researching his book on Georg Cantor in earnest in late 2000. This book on mathematics took so much longer than he had anticipated and greatly distracted him from writing fiction. Some of the first emails Wallace sent were to a graduate student he hired to check some of his proofs and mathematical reasoning. Unfortunately, she introduced as many errors as she fixed and Wallace had to complete another round of revisions after the hardcover was published.

Wallace did have a computer at home in 2000, but he tells Steven Moore in April of that year “I don’t even have a modem yet, which people here regard as weird and Ludditic, but mostly I just don’t want to have to see any more ads than I already see every day.” The David Wallace of The Pale King says “I can’t think anyone believes that today’s so-called ‘information society’ is just about information. Everyone knows it’s about something else, way down.” Giving up pen and paper for a username and a password is a significant shift, a loss of control, and one Wallace approached with skepticism and dread.

In February of 2001, he was still faxing cuts of “Tense Present” to Harpers via “Borrowed Fax.” Wallace loved, or at least had fun with, the now obsolete convention of the Fax Cover Sheet. In fact, he held on to faxing until at least 2004. He was an extremely creative person and the impulse to draw and scribble and add smiley faces and the general lexical mess he could make of a page were stifled by email. However, email did not stop him from sending handwritten postcards and letters—a practice he continued until the end. And he did eventually adopt a unique email signature – /dw/ – and adopted basic smiley-face emoticons.

Wallace’s first email address was tpdritz@msn.com. Why he chose msn.com over the more popular Hotmail, Yahoo, and AOL, remains a mystery. Who knows? The name TPDRITZ appears to be a fictional character name, as “Herb Dritz” shows up in The Pale King as a Schedule F Specialist, but it’s obvious why he didn’t want an easily recognizable handle: if word got out that DavidFosterWallace@MSN.com actually reached the Man Himself, he would surely have been inundated by mail from strangers, which he would have felt obligated to respond to. No doubt some part of Wallace found the relative anonymity of the internet very appealing.

“I allow myself to Webulize only once a week now,” he wrote to Erica Neely in July 2001. However, most of his writing at that point still began with a pen and not a keyboard. When he moved to Pomona in 2002, he kept the tpdritz handle on the Pomona email system, but in the “real name” field he added “Ryan Trask.” The only literary connection I could find to that pseudonym was the character Myrnaloy Trask from his story “Order and Flux in Northampton.” It served as a good foil, though, because it sounds like a student’s name.

Wallace later switched his official work email account to Comcast rather than Pomona. His personal email address was turdnagel@comcast.net and his school email was ocapmycap@comcast.net. Obviously, Ocapmycap is a reference to Walt Whitman’s poem about the death of Abraham Lincoln (made famous in Dead Poets Society, wherein the earnest young students are told they can address their literature professor as “O Captain My Captain” if they feel daring enough). It’s a testament to both Wallace’s humor and belief in the triumph of art that he had his students effectively address him as such by emailing ocapmycap@comcast.net if they were daring enough to email him at all.

“Turdnagel” is also mentioned in The Pale King as a diminutive of sorts, a cross between a plebe and brown-noser. But the word also shows up in Don Delillo’s “Players.” I think it’s just a funny, scatological word that Wallace liked. He also called one of his dogs “Turdnagel.” Lee Konstantinou has a theory that the term is related to philosopher Thomas Nagel. It also appears that Wallace used the handle “turdnagel” to play a game of online chess in Spring 2008 on the website RedHotPawn.

Online chess: http://www.redhotpawn.com/profile/playerprofile.php?uid=428264

Turdnagel – joined 23 Mar 08 / last move 10 June 08

He stopped using Pomona’s email system altogether in 2004 and at some point in late 2006 or early 2007 he consolidated all of his email correspondence into ocapmycap@ca.rr.com.

The printouts in the archive do not include any of the attachments included with the emails Wallace and Nadell sent to each other. Future archivists should make sure they are included in the original acquisition and writers should take care to preserve original attachments whenever possible. Curiously, there is no evidence in the archive that Wallace emailed anyone at Little, Brown directly – he always emailed his agent or wrote paper letters to Little, Brown. He was somewhat secretive about his own email habits and kept his authorial distance.

If we examine the email printouts closely, we see a few details—like the fact Bonnie Nadell’s email client is Yahoo—but not as much “personality” comes across as in his handwritten letters. And these plain white pieces of paper really require no special archival handling, nothing remotely approaching that sheepskin behemoth I saw. The copy paper could easily be Xeroxed without any damage done to the originals. I assume that most if not all of the electronic versions of these files are lost or deleted now and we will have to rely on the printouts for the rest of eternity. Of course, this is not ideal. The printout itself, with its corporate logos and metadata and uniform fonts, are deeply banal and boring. I would hope that some forward-thinking author preserves digital backups of their email archive (and computer files in general) or even shares all of their account passwords with their literary executor or spouse. One could envision a virtual inbox where scholars might be able to search and emulate a logged-in version of an author’s own email.

There are hundreds of Wallace’s letters in the Ransom Center’s archive, but there is just no way that the Ransom Center has anything near a fraction of the emails Wallace sent or received. It will be interesting to see how many of them Stephen Burn will be able to collect for his upcoming volume of letters, but it’s highly likely that some of the emails Wallace sent to translators, friends, agents, editors, and colleagues, have already been deleted or lost. Most of his correspondents are still living and some consider the emails and letters too precious or private to share with fans or scholars. So we will never have a complete picture of his correspondence—and no idea really how incomplete it is.

Presidential scholars are already faced with this task – how do you archive and collect an administration’s digital assets, which might include everything from eight years of tweets, Facebook posts and comments, millions of staff text messages, emails, Instagram pics, Reddit AMAs, and the administration’s unique data architecture? Do you try to print it all out and put it into manila folders? It makes much more sense to turn over that vast amount of data and metadata to scholars in a digital format, so why haven’t authors and literary archives followed suit?

The value of an author’s archive lies not just in the amount of information it contains, but also in the shared sense of identity we create about literature by collecting these specific things and that in turn teaches future generations wherein our values lie.

The scholar who requested that huge processional volume in the reading room told me that it required up to five animals to be slaughter to provide the skins necessary to craft a single page. Hundreds of animals were led to slaughter to preserve a single processional song. The current leading lights of literature could preserve their correspondence for future researchers with considerably less bloodshed—just a drop or two of foresight.