wallace-l Interviews David Lipsky

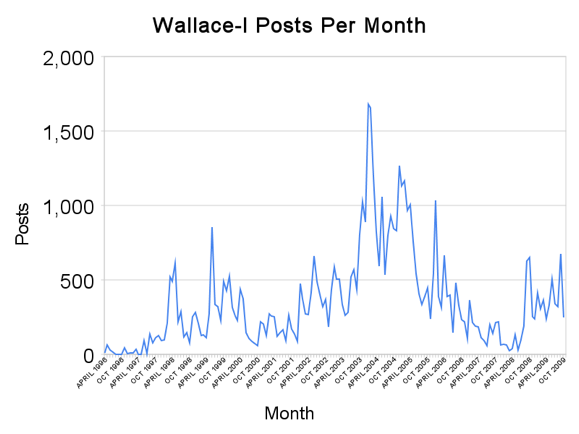

Posted: April 2nd, 2010 | Author: Matt | Filed under: DFW | Tags: David Lipsky, DFW, interview | 2 Comments »In 1996, David Lipsky spent five days with David Foster Wallace at a pivotal moment in Wallace’s life—the very week he finished promoting Infinite Jest. Lipsky never wrote the resulting Rolling Stone article, but now the interview is published in full: Although Of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself: A Road Trip with David Foster Wallace (Broadway Books). Rarely do we get to see such an extended portrait of a writer during the moment their masterwork enters the public arena.

David Lipsky graciously allowed members of the wallace-l mailing list to submit questions about his time spent with Wallace, Wallace’s life and writing, and other details despite the list not having yet read the book. Lipsky’s answers defy the common convention of simplicity in service of delving into deeper issues like how Wallace’s writing was able to connect so deeply with readers and what his death therefore means (and also what kinds of music DFW was into). As you’ll see, in the book and in interviews, Lipsky’s preference is not to speak for David Foster Wallace, but to hand you back a thick slice of Wallace’s own words and then ask for your side of the conversation. Despite his distaste for large, public gatherings where he was the focus, Wallace was a natural conversationalist. And, as you’ll see here and in Although Of Course, so is Lipsky

Matt Bucher: Many of the members of the list have followed Wallace’s career from the beginning. What’s surprising about your interview with him is that he seems to be willing to talk about parts of his life he’d never discussed with any other journalist in any other interview. By the end of the trip, he told you stories we’ve never heard before. Were you aware of that at the time? Why do you think he was so open and honest with you?

David Lipsky: I wasn’t at the time—I could see that he was trying very hard (he was working) to get his answers right. Particularly in the last two days, he keeps turning the tape machine off as he collects his thoughts, sort of air-writing, then turning it back on when he’s got things the way he wants. I think he could tell how much I loved his work and he also knew my tastes: we’d spent days talking books and movies, and there was (Nabokov, DeLillo, not Updike) a good bit of overlap. And there was also just the time and distance. I joke in the book that he got open and honest by the Henry Ford principle: any people driving together more than forty miles can’t help becoming comfortable.

But during the drive, it didn’t seem like he was being honest and open; it just felt like a conversation. When I reread the talk once I got home, I was amazed by it. Really: why had he told me that stuff about McLean, about Michael Pietsch’s edits and printing the book in nine-point font? He could have skipped all of it, and nobody would have been the wiser. But also I think that’s just him. One of the lessons I get from his work is personal non-editing: giving a chair to all thoughts and impressions, which will include the best and the ugliest. It’s why other writing often seems comparatively flat: more formal and more ritualized, more like nametag conversations at a convention. He’s inviting in every thought. (So much David was afraid critics would notice. “But the fact that she [Michiko Kakutani] would think that this was just every thought I seemed to have for three years put down on the page, just made my bowels turn to ice. Because that was of course the great dark terror when I was writing it. Is that that’s how it would come off.â€) So if he was going to talk about his very grim time at Harvard and McLean hospital, or nice stuff at Amherst and Arizona, he was going to talk about it all the way.

I also think we were having fun—I mean I think the book is a record (him kidding me about wet dreams and my Updikephilia) of us having fun. I was sitting on the living room carpet, him playing Brian Eno, his dogs kind of batting me over, all of which is conducive to being open. The trip, aside from everything else, was a very good time. The reading was good tense fun. (Every time I read that guy on the signing line asking about David’s “heart song,†I smile. Or the escort decoding one of his jokes. Or his jokes about escorts.) The plane ride was fun, the mall was fun. All of which is one big reason I wanted to do the book: to give people the chance to be around him and to spend those hours the way I had. And I hope and like to think one reason is he was having a nice time too.

But here’s the reason David gives. We’re talking about LaMont Chu from Infinite Jest, how it seemed to me that LaMont’s anxieties about fame as a tennis player were pretty clearly a stand-in for a young writer’s drive for reviews and profiles. He laughed a sort of dark, exposed, pleased laugh. “Only a writer under, like, thirty would have known that that came out of bitter truths.†I said he must’ve guessed someone would notice and ask. “Except only another writer would. That’s the good and bad thing about choosing you to do this. I’m serious, man—like this would have been over a day ago if you hadn’t been somebody who writes novels.â€

Maria Bustillos: When you met Wallace, did you get a sense that he was an ongoingly troubled man? Could you ever have guessed, at that time, that his life would end this way? Did the first-person account of his problems with depression strike you as indicators, as possible harbingers of a catastrophic breakdown? Will you comment on how his suicide has affected your own attitudes toward depression and mental illness?

David Lipsky: First — I’m sorry, talking about Wallace puts me in a good mood — I’d like to say to Maria, and everyone on wallace-l, that very nice thing Wallace taught all of us how to do. Which is to compress sentences, spring-load them, by wedging in what would otherwise be four or five dribbling words after the sentence’s action as a modifier. That “ongoingly troubled man†is a great Wallace front-loaded sentence. Just the way my last one was. A great writer changes the way everyone unconsciously thinks, writes, speaks. He taught thousands of people how to do that.

Not for a second—but to jump ahead, I don’t like thinking about his suicide, and another big reason I did the book was to not have that be the picture people had of him. It’s why I pushed the afterward to the front: so the last image you get, when you close the book, is of Wallace happy, alive, thirty-four years old, confident, leaving for a dance. (The other reason I don’t think many people outside wallace-l will get: I thought how Infinite Jest begins in Glad instead of Y.D.A.U., and A Supposedly starts with him recalling the Nadir at the Fort Lauderdale airport coffee shop. A friend of mine was reading the book at my house and looked up and said “Wallaceian,†without being able to put a finger on why. So I’ve focus-grouped this.)

But about his suicide: I don’t think of it as an expression of his will. The friend who read the book actually then had an argument with me about that. I think of it as a medical story, a prescription drug story. I interviewed a Harvard Medical School professor, and he understood the story immediately: if you’ve been on the same agent for a very long time (“agent†is the term of art, and David’s agent, as everyone here knows, had been Nardil for two decades) it’s impossibly hard to get off it, and there’s also a small chance that you might not be able to come back on. That’s what happened to David. So my attitude towards depression and mental illness is stay with medications that work. I don’t think his death had anything to do with The Pale King or any other personal situation; if he hadn’t wanted—for smart, legitimate health reasons—to go off Nardil, Maria and all of us wouldn’t be thinking about this.

I was shocked when David died. I got an email that I was pretty sure was a mistake or a very odd joke. David talks a lot in the book about depression; but he talks about it as something in his past, an awful place he visited, got to know gruesomely well, and then fought his way out of. He called what happened to him, around when Girl came out, “the most horrible period†he’d ever gone through. “And I admit I have got a grim fascination with that stuff. I’m not Elizabeth Wurtzel. I’m not biochemically depressed. But I feel like I got to dip my toe in that wading pool, and not going back there is more important to me than anything. It’s like worse than anything.â€

He didn’t even call what happened to him a depression. “It sounds weird—but I think it was almost more of a sort of an artistic and religious crisis, than it was anything you would call a breakdown. I just—all my reasons for being alive and the stuff I thought was important, just truly at a gut level weren’t working anymore…It may be what in the old days was called a spiritual crisis or whatever. I think I had lived an incredibly American life. That, ‘Boy, if I could just achieve X and Y and Z, everything would be OK.’ And I think I got very very lucky. I got to have a midlife crisis at twenty-seven. Which at the time didn’t seem lucky; now it seems to me fairly lucky. But now maybe now you can understand. That period, nothing before or since has ever been that bad for me. And I am willing to make enormous sacrifices never to go back there.â€

So, to move back, I may have been naive or not paying the right kind of attention. I didn’t see any harbingers. He was just a huge amount of fun to be with — so smart to talk to, so awake to everything. (There’s that “record digitally†joke I talked about with Mark Athitakis. That’s not a depressed mind at work. That’s lightning.) And his work—even when it goes dark—always has the tremendous buzz and energy of perception in it. That’s what he was like to be with in the car. He told me some very hard stuff. But if you’d asked me to name the most mentally healthy American writer in August of 2008 I would have said, without hesitation, “David Foster Wallace.†I cried, in 2005, when I read the last two pages of “Good Old Neon.†Especially the last parenthesis: “considerable time having passed since 1981, of course, and David Wallace having emerged from years of literally indescribable war against himself with quite a bit more firepower than he’d had at Aurora West.†That was the sound of a man at peace. I don’t cry in books but I cried there.

He’s seemed warm and wise and kind—even when he gets pissed off at me, he forgives it and stays kind. There’s a part in the book with a quote from Jonathan Franzen, who I’m sure you all know was his last decade’s closest friend. Franzen says, “Does it look now as if David had all the answers?†His dying the way he did doesn’t alter my answer to that question. There’s stuff he says in the book that I think of all the time. Really unexpectedly. If I’m quizzing myself on what I should or shouldn’t do (that’s more the kind of reading I do: I turn to books for advice; the whole library is self-help), or thinking about books, or why I love certain kinds of writing: A David remark will pop up. I think the way his life ended was a medical error—the thing from his twenties coming back, a brain suddenly deprived of what had become a necessary element—but for me it doesn’t shine its way back through his life and work to the beginning. And looked at from the other side, from when I parked near his lawn, nothing in the five days together made me guess this.

Brian Cochran: Would this book really be coming out now if he were alive?

David Lipsky: That’s a good question, Brian, and no, I don’t think it would be. I read the week again about two and half years ago and loved it, and was trying to think of some way it could work as a mammothly long piece. Because there David still was, happy and open, talking about things I hadn’t read him talking about. And on the page, there was the preserved experience of that time, what he was like when he was young.

But one reason I wanted to publish this book, as I was answering to Maria, was an image coalescing around David that was heavy, sad, dark: What he’d done, what it meant. And there was a chance that people would begin to picture him as always grim and lightless, a cautionary tale, which isn’t at all what he or the books are like. (His books and thoughts are best-case. And they’re comic.) There’s something his sister said, in the beginning of the book. “My own anxieties are many. My brother was a hilarious guy, a quirky, generous spirit, who happened to be a genius and suffer from depression. There was a lot of happiness in his life. He loved to be silly, he made exquisite fun of himself and others. Part of me still expects to wake up from this, but everywhere I turn is proof that he’s really most sincerely dead. Will he be remembered as a real, living person?†That’s why I wanted to do this, and do it this way: David in action, not as a story moving towards an end we all know. And with the reader seeing that that—generous, funny, happy—was what he was like to be around.

Allan Wood: Is there any indication that DFW knew or hoped or imagined that IJ would be the important novel it has become? We’ve read Pietsch saying that after he read some of the manuscript, he wanted to publish IJ more than he wanted to breathe. Did Wallace give any indication that he felt he had really nailed it?

David Lipsky: That’s funny, Allan. I really smiled when I read this, because I asked the exact same question, in two parts, in more or less the exact words that you did.

Lipsky: “Michael Pietsch’s presentation. He went to his sales force, at their conference, and said, ‘This is why we publish books.’â€

David: “I wasn’t there. I know he really liked it. And I know he really read it hard, because he helped me—I mean, that book is partly him. A lot of the cuts are where he convinced me of the cuts. But also, editors and agents jack up their level of effusiveness when they talk with you, to such an extent that it becomes very difficult to read the precise shade of their enthusiasm. What’s being presented for you and what they really feel.â€

And then at little later I asked your second part—exactly the way you did.

Lipsky: “But when did someone come to you and say, ‘David, you really nailed it’?â€

David: “It’s very odd, because Michael would say really nice stuff to me, and he’d say it in the context of having critical suggestions. So I could write it all off as you know, Well he, this is the sugar that’s making the medicine go down.

“And Charis [Charis Conn, his first Harper’s editor] liked it, but Charis likes everything I do. There was some stuff—because Mark Costello is really good friends with Nan Graham, who knows more about the publishing industry than anybody. She was DeLillo’s editor, which as far as I’m concerned does it for me. So I can remember—when they did this postcard thing, and they wanted to do signed bound galleys and sent me boxes full of paper—my not knowing what to make of it. And calling Mark and having Mark find out, I presume from Nan, that this meant that they were going to support the book, and that they were into the book or whatever. Which given that the book is a thousand pages made me think that they thought it was a pretty good book.â€

I think David hoped it’d be a great book. Mark Costello told me David announced to him all at once in college, “I want to write books people will read 100 years from now.†David said he worked harder on this book than any other. But he was immensely prickly with himself—he graded himself on a very steep curve—so he didn’t take the early reviews seriously. He said, “The book takes at least two months to read well. If two years from now, I’ve got people who like have read the thing three times, who come up and say, ‘This thing’s really fucking good,’ then I’ll swell up…like, if I have a bunch of conversations, like with this guy Silverblatt [Michael Silverblatt, host of NPR’s Bookworm], or with Vince Passaro, or with like David Gates, somebody who clearly read the book closely. And a bunch of people are saying it’s good, then I’m probably gonna start feeling wholeheartedly good about the book. As it is, there’s a kind of creeping feeling of a kind of misunderstanding.â€

He also said a great thing about how you start to write a really good book. “I think I have a really low pain threshold. I think the ‘I’ll show people,’ or ‘People are really gonna like this’— thinking that way has hurt me so bad. That when I’m thinking that way, I’m not writing. That that’s this thinking in me that’s gotta reach this kind of fever pitch, and then break. In order for me to even start—not to get in the groove, but to get started…And I would still hear the, ‘This is the best thing ever written,’ and ‘This is the worst thing ever written.’ But it’s sort of like, you know how in movies there will be a conversation, and then that conversation gets quieter, and a different conversation fades in. I don’t know, there’s some technical word for it. Just, the volume gets turned down. . . I mean, this is absolutely the best I could do between like 1992 and 1995. And I think though that if everybody’d hated it, I wouldn’t be thrilled, but I don’t think I’d be devastated either. It’s about that it got, it became alive for me.â€

George Carr: What do you know about DFW’s decisions about what to submit for publication and what to keep tinkering with? And were there any early pieces that he later regretted publishing or later disavowed?

David Lipsky: He’s very funny and negative about Broom. He’s talking about how some reviewers use strong early work as a club to beat later stuff. “The nice thing about having written an essentially shitty first book is that I’m exempt from that problem. There were a lot of people who really liked Broom of the System, but unfortunately they’re all about eleven.â€

He also said, about Broom, “I wrote Broom of the System when I was very young. I mean, the first draft of that was my college thesis. There are parts of it that I think are good. But it’s—I wince.†I liked Broom, so we went over this some more. David had written a 17-page letter to Gerry Howard, his editor, explaining why he’d resist certain changes, especially to the last pages. I asked whether he’d reread the letter.

“Oh sure…It’s a brilliant little theoretical document, unfortunately it resulted in a shitty and dissatisfying ending, right? And in fact it was a very cynical argument, because there was a part of me—this was a year and a half after I wrote it, and I knew that that ending, there was good stuff about it, but it was way too clever. It was all about the head, you know? And Gerry kept saying to me, ‘Kid, you’ve got no idea.’ Like, ‘We wouldn’t even be having this conversation if you hadn’t created this woman named Lenore who seems halfway appealing and alive.’ And I couldn’t hear. I just couldn’t hear it. I was in…Dave Land.”

“I had four hundred thousand pages of continental philosophy and lit theory in my head. And by God, I was going to use it to prove to him that I was smarter than he was. And so, as a result, for the rest of my life, I will walk around…You know, I will see that book occasionally at signings. And I will realize I was arrogant, and missed a chance to make that book better. And hopefully I won’t do it again. It’s why I will not run lit-crit on my own stuff. And don’t even want to talk about it.â€

It just occurred to me: I mention in the book that David is carrying a Heinlein novel around on his tour—reading it on the plane, in his hotel. I didn’t give the title. It was Stranger in A Strange Land. Now I wonder if that might have been a small meta-joke on his part: how odd it felt for him to be on this tour, surrounded by all these eager-to-be-helpful book people.

Extra credit Carr point: After he wrote “Westward,†he had a terrible time getting started on anything else. He wrote a long piece on adult film that’s different from the AVN piece, but never published it. (“I have some really riveting taped interviews with porn stars, too.â€) And he struggled with fiction. “I started hating everything that I did. I remember I did two different novellas after ‘Westward,’ that I worked very hard on, that were just so unbelievably bad. They were, like, worse than stuff I’d done when I was first starting out in college. Hopelessly confused. Hopelessly bending in on themselves…â€

George Carr: Rumors about DFW’s drug habits are plentiful but unconfirmed. Was there a period in DFW’s life when his recreational drug use was casual (non-addicted)? And was there an event that signaled/caused a shift to more self-destructive use?

David Lipsky: He talks about it. I think he was casual as a teen. We’re talking about TV, and how he faced in-house restrictions, a screen-ration per day. I asked if he ever went over to friends’ homes to sneak a little extra. “When I went to my friends’ houses we would do bones,†he says. “That’s what I went to friends’ houses for.â€

He began smoking (like Hal) on his tennis team. “I started to smoke a lot of pot when I was fifteen or sixteen, and it’s just hard to train when you smoke a lot of pot. You don’t have that much energy. So I was still going to tournaments. But I was mostly doing it, going to hang out with the guys and party. And I was getting to the quarters instead of the semis of these tournaments. And there was just a general kind of slippage. Fifteen, sixteen, something like that. I mean, starting really to kind of like it.†He says, “I smoked a reasonable amount of dope, particularly in college and grad school. And…uh…and drank a lot.â€

I don’t think, George, that it was an event: it was a kind of sadness that came to him around the time he finished “Westwardâ€â€”which he felt had kind of ended one course in his fiction. “It was after finishing that and doing the editing on that, that I remember getting really unhappy.†He was at Harvard, having the trouble writing that you asked about a little above. At that point, it was mostly alcohol. “I was really stuck. And drinking was part of that. And it’s true that I don’t drink anymore. But it wasn’t that I was stuck because I drank. I mean, it was more that—and it wasn’t like social drinking going out of control. It was like, I really sort of felt like my life was over at twenty-seven or twenty-eight. And that felt really bad, and I didn’t wanna feel it. And so I would do all kinds of things: I mean, I would drink real heavy, I would like fuck strangers. Oh God—or, then, for two weeks I wouldn’t drink, and I’d run ten miles every morning. You know, that kind of desperate, very American, ‘I will fix this somehow, by taking radical action.’ And, you know, that lasted for a, that lasted for a couple of years.â€

A friend emailed, very generously, to say I should quote David less when talking about him—but I love his work so much I’m going to go ahead anyway. I mean, that’s the book’s point, to let David’s story come from him. So here’s another reason why he drank, and apologies in advance if my friend reads this. “I was sort of a joyless drinker. I think I just used it for anesthesia. I also remember, I mean really buying into—I don’t know how much you yourself escaped this. But it’s fairly hard to get a book taken when you’re in grad school. And to get a whole lot of—to get your juvenile dreams fulfilled real fast. I think I had this idea of: you know, went to Yaddo a couple times. And I saw that there’s this whole image of the writer as somebody who lives hard and drinks hard. You know, is found in amusing postures in gutters and stuff. And I think when you’re a kid, and you don’t have really kind of any idea of how to be what you want to be, you fall for these sort of cultural models. And the big thing about it is, I don’t have the stomach or the nervous system for it. I get really, really drunk. Then I’d be sick for two days. Like sick in bed, like a bad flu. Just kind of debilitated.â€

A bit later he says, “I’m also aware that some addictions are sexier than others. I think my primary addiction in my entire life has been to television. And the fact that I don’t have a television, but now enjoy sitting in the second row of movies where things blow up—this is not an accident. But I am aware that that’s of far less interest, than the idea of heroin, or of some grand, you know, something that confirms this mythos of the writer as some sort of titanic figure with a license to. . .â€

Extra Carr Point 2: Stopping, to his surprise, didn’t offer an immediate improvement. “The scary thing to me was that…I mean I was going through a lot of confusions about sort of writing, and art, and all this kind of stuff at the time. And I thought quitting drinking would help. It made things worse. I was more unhappy, more scared, more paralyzed when I quit drinking. And that scared me. And I think the period that I really consider a kind of dark— The period that I think you know about, where I went in on suicide watch, was months after I had stopped drinking.â€

Jonathan Goodwin: Did you happen to chat with Wallace about why he chose to go to the U of Arizona MFA program, esp. given his later open disdain for how fiction was taught there?

David Lipsky: I did. I was curious too; it’s not in the book. For better or worse—and to his annoyed and still-sore surprise—he didn’t get into Iowa, which is probably the best-known writing program. And he couldn’t attend Hopkins, since John Barth taught there: “I was so in thrall to Barth, I just knew it would be sort of a grotesque thing.â€

He thought Arizona hadn’t been his sharpest idea. “In a way I made a stupid choice: They are a highly, incredibly hard-ass realist school. I was doing very abstract stuff back then, most of which was really bad. But it was just funny, because it’s also a really careerist place. And they had to go from almost kicking me out, to this sort of tight- smiled, ‘we’re proud of you,’ you know, ‘that you’re a U of A man.’ I felt kinda embarrassed for them… It was just so delicious. I had gotten to have unalloyed contempt for them, they showed what they were like. They didn’t even have integrity about their hatred.â€

On the other hand, he felt very lucky to have found Tucson. “Arizona is the only place—it’s the first place I’ve ever lived, that I truly absolutely loved. Like geographically. The warmth and the—have you ever been there? It’s an interesting town, you can live there on practically nothing, because all the houses have carriage houses behind them that people rent out for like $150 a month. And it’s a great—it’s like a town preplanned for Bohemia, almost. And there’s a whole lot, there’s a really cool like leftist cultural world. Because a lot of grad students just end up teaching part-time at the U of A and living there for like ten, twenty years. And it’s just really gorgeous.â€

Lisamichelle Davis: It seems to me that the key to the heart of “Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way†(as opposed to the work’s many fun, ironic, meta-, and po-mo features) is Wallace’s distinction between the statements “you are loved†and “I love you.†The final sentence of the story, “You are loved,†not only highlights that distinction (which Wallace discusses in detail earlier in the story), but also suggests that the narrator and/or author believes that “you are loved†is the far more important of these two statements. Why? As human beings, what do we gain from feeling that we are loved that does not or cannot also flow from feeling that a particular person loves us? What does that say about Wallace’s views on loneliness and connection?

David Lipsky: Lisamichelle, I think you kind of slyly answered that question yourself at the end. Marie Mundaca wrote a beautiful essay at I think hipsterbookclub.com, that ends with her walking home after leaving the Little, Brown offices, having finished up the design for This is Water, seeing the words “You are loved†chalked on the pavement. She has a photo of it in the piece. And that’s the thing I flashed on just now. Aside from that moment’s eeriness, just how good and broad those words feel: “You are loved.â€

This is just me as a reader. I think there’s a fear, in David’s work — it’s at the margins of the stuff about Hal — of being loved only for a specific achievement. And then there’s a different fear, which Orin seems to have, of the implied possession — of being pocketed when someone says “I love you.†(On the other hand, David says a kind of tetherless, emotional-brakes-locked sex can leave a person feeling “rather lonely. And if you’re thinking of Orin in the book a little bit, that’s fine.â€) “You are loved,†seems boundless and non-determinate. It means the whole of you, wherever you go: it’s a wide map you can walk over anywhere. I think David, from the little I got to know him, had very keen receptors for fraudulence: his own, where he found it and tried to excise it, and others peoples’. My favorite story of his is “Good Old Neon,†where that’s not just the subtext but the whole thing. (A few days ago, I found this great question on “Ask MetaFilterâ€: “How Do I Stop Being Neal From ‘Good Old Neon’?†A bunch of people tried to answer—this one, presumably, came from someone in the hospitality industry: “This is a very vague question, but the first thought that came into my head is ‘travel.’ Just buy a plane ticket and go there.â€) And what makes Neal finally want to leave is learning that his own problem, inability to love, is such a cliché it’s a sure-fire laugh-getter on Cheers. And there’s the Depressed Person in “The Depressed Person,†who can’t feel anything other than her need for relief; that’s how other people loom to her, as relief. And then the pop quizzes in “Octet†seem to all be about tipping the answerer towards selflessness. Away from “I love you,†towards that “You are loved.†(Think of the difference if you’re serving a meal: “I fed you,†“You are fed.â€) And in “Adult Worldâ€â€”this has become a tour of the Wallace short-fiction oeuvre—happiness steps into the Roberts’ marriage when the couple learns to, essentially, both masturbate. That’s a comically successful marriage, no love at all. Wallace ends with the dry line, they were “…ready thus to begin, in a calm and mutually respectful way, to discuss having children [together].â€

I’ve kept thinking of something David says near the end of the trip. “There are all kinds of reasons for why we’re so afraid. But the fact of the matter is, that the job that we’re here to do is to learn how to live in a way that we’re not terrified all the time. And not in a position of using all kinds of different things, and using people to keep that kind of terror at bay. That is my personal opinion.†For me, that’s the line I think of, as the difference between “I love you†and “You are loved.†It’s giving something without wanting anything back. It’s the warmest thing in the list of lessons learned by the residents at Ennet house.

David Hering: Did Wallace’s feelings about “Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way†change once Infinite Jest had been published and well received? Was he able to accept that piece more or did he still feel that he didn’t like it?

David Lipsky: More “Westwardâ€â€”which I guess is why it’s such an ideal group read. David wasn’t sure yet how Infinite Jest had been received; he said, very self-effacingly and with a good canny knowledge of the book business, that he’d have to wait a couple years to find out if it was any good. He was happy to offer that clear negative estimation of Broom. Which he thought was “in many ways a fuck-off enterprise.â€

But “Westward†was one of the few things he wrote, he says, that got up off on the table and walked on its own. “You talk about, I’ve said that three or four times something came alive to me, and started kind of writing itself, and that was one of them. Although it wasn’t a very happy experience.â€

So I never got the impression he didn’t like it: he loved it, it had been important for him, but writing became a lot harder afterward. I’m going to try to combine some different things he said about “Westward†into one block. I think, for him, that novella was the closing the office and packing the bags of an early writing self.

“I really think that for me just personally, ‘Westward’ was this real seminal thing. Like I really felt like I’d killed this huge part of myself doing it…. This is what’s embarrassing. I know it’s not that powerful for anybody, but I really felt like I’d blown out of the water my whole sort of orientation to writing in that thing. And had kind of written my homage and also patricidal killing thing to Barth… That story at the end of Curious, which not a lot of people like, was really meant to be extremely sad. And to sort of be a kind of suicide note. And I think by the time I got to the end of that story, I figured that I wasn’t going to write anymore… Well, I just thought I’d, I just didn’t see the point of it anymore. I mean, the stuff that I was interested in seemed—I mean, I really felt like ‘Westward’ had, at least for me, had sort of folded it up into this tiny, inï¬nitely dense thing. And that it had kind of exploded.â€

It’s after “Westward†that things, he says, got trickier and grimmer at Harvard. But when I told him I’d enjoyed the story, he was very pleased. The strange thing is, he’d written the first draft by hand—and then came to New York for an Us photo shoot and it was stolen from his trunk. He found the airline bag it was in, and walked around Washington Square hunting for the pages. And then he went back to Yaddo and wrote a complete new version in a week. “The first half was real different,†he says. Which meant he loved the story so much that he wrote it, and let it write itself, twice. Which I think you’d only have the heart to do if you were loving something.

Dan Scharf: I’d be interested to know if DFW talked to you about future professional plans, i.e. did he have ideas for books or essays that he wanted to write in the future (other than The Pale King), did he ever think of writing in any other mediums (always wondered if he ever thought of writing a screenplay or play)?

David Lipsky: I’ve read somewhere his saying he didn’t want to write screenplays because he liked to maintain control of both sides of the chess set. He said a smart thing about the difference between movie-work and prose-work; he’s just described himself as both a bit of an exhibitionist and shy. “At the same time, I think that somebody who’s writing, has part of their motivation to sort of impress themselves and their consciousness on others. There’s an unbelievable arrogance about even trying to write something—much less, you know, expecting that someone else will pay money to read it. So you end up with this, uh…I think exhibitionists who aren’t shy end up being performers. Plying their trade in the direct presence of other people. And exhibitionists who are shy find various other ways to do it. I would imagine that maybe film directors, it’s the same way.â€

He was just very enthusiastic, incredibly enthusiastic. He says, “You know, I’m thirty-four. And I’ve finally discovered I really love to write this stuff. I really love to work hard. And I’m so terrified that this—that this is going to somehow twist me. Or turn me into somebody whose hunger for approval keeps it from being fun. I mean, I think Infinite Jest is really good. I would hope that if I keep working really hard for like the next ten or twenty years, I can do something that’s better than that. Which means I’ve gotta be really careful, you know?†And he says, “I know this is gonna sound drippy and PC. I’m just, I’m really into the work now. I mean it’s really—and I feel good about this. Because, you know, we wanna be doing this for forty more years, you know? And so I’ve gotta find some way to enjoy this that doesn’t involve getting eaten by it, so that I’m gonna be able to go do something else. Because being thirty-four, sitting alone in a room with a piece of paper is what’s real to me.â€

Barbara Warren: I’m interested in artists’ marriages and families. What did David think/say/feel/hope for/fear in the domestic realm?

David Lipsky: I am too. I think he was. He’s very clear about it. The year before we spoke, his sister had gotten married. “And it was a tough summer. It was very hard for me, because I would like to be married, and I would like to have children. And it was hard for me when my sister got married, who’s like younger than me.â€

But he anticipated it’d be difficult—that he didn’t work on an especially marriage-conducive schedule.

“I think if you dedicate yourself to anything, one facet of that is that it makes you very very selfish. And that when you want to work, you’re going to work. And you end up using people. Wanting people around when you want them around, but then sending them away. And you just can’t afford to be that concerned about their feelings. And it’s a fairly serious problem in my life. Because, I mean, I would like to have children. But I also think that the sort of life that I live is a pretty selfish life. And it’s a pretty impulsive life. And I know there’s writers I admire who have children. And I know there’s some way to do it. I worry about it.â€

And he missed the nice parts of a marriage, as Infinite Jest succeeded. “I really have wished I was married, the last couple of weeks. Because yeah, it’d be nice to have somebody to—you know, because nobody quite gets it. Your friends who aren’t in the writing biz are just all awed by your picture in Time, and your agent and editor are good people, but they also have their own agendas. You know? And it’s fun talking with you about it, but you’ve got an agenda and a set of interests that diverges from mine. And there’s something about, there would be something about having somebody who kind of shared your life, and uh, and that you could allow yourself just to be happy and confused with.â€

Charis Woods: Given DFW’s frequent use of nightmares in his work (the face on the floor in IJ, Gately’s dreams in hospital, Oblivion and more…), I was wondering whether he ever talked about having terrifying dreams.

David Lipsky: Charis, it never came up. He mentioned that he was an uneasy flier. But then on the airplane out (flight to Minneapolis), he was totally relaxed and happy, and then on the way home (tour over) he dropped the Heinlein in his lap and fell asleep. I watched the clouds and landing lights out the window behind his profile.

My first night in his house, we didn’t get a huge amount of sleep. One of his dogs (Jeeves, who’s in the cover photo with him) got caught on a cycle. Howl, pause, repeat. Finally, David said, “Jeeves—enough.†Maybe noisy active dog ownership precludes nightmares.

He says he took a lot of instruction from the way David Lynch deploys nightmare on film. “That whatever the project of surrealism is works way better if 99.9 percent of it is absolutely real. And that’s something, I wouldn’t even be able to put it that clearly if I didn’t teach. Where I see my students, you know—‘not enough of this is real, you know?’ ‘But it’s supposed to be surreal.’ ‘Yeah, but you don’t get it.’ Surrealism doesn’t work. I mean, most of the word surrealism is realism, you know? It’s extra-realism, it’s something on top of realism. It’s that one thing in a Lynch frame that’s off. That if everything else weren’t picture-perfect and totally structured, wouldn’t hit. Wouldn’t punch the viewer in the stomach the way that it does.â€

Trent Cable: What kind of roadtripper was Wallace? Did he like to snack and drink, if so what were his snacks and drinks of choice? What did he like to listen to when there were breaks in conversation–CDs (if so, what), local stations, NPR?–and I guess more generally, what his taste in music was and what was the level of passion? Did he like to play road games? Stuff like that.

David Lipsky: No road games. Complaining about other, lane-jumping drivers (“this guy is a true assholeâ€), an open Diet Pepsi can to spit in. His music tastes were pretty eclectic. He loved the REM song “Strange Currencies†(“I mean, I will find one or two songs—I listened to ‘Strange Currencies’ over and over again all summerâ€). He knew the music he liked very well—the way Nabokov could track certain themes and lines across a centuries’ novels—so well he could hear where they were being picked up by other artists. On the other hand, he says, “I have the musical tastes of a thirteen year old girl.†He listened to Nirvana while writing Infinite Jest; and also to “this woman named Enya, who’s Scottish.†(On Nirvana, it was only because a grad student had given him a tape; he was that kind of listener, too—he got his playlists from other people.)

Ben Timberlake: Did he have any surprising ethics and principles ready at hand? Do you ever wish to be able to read his writing without having had a closer relationship to him than most readers? I add my thanks to Lipsky for considering questions from the list.

David Lipsky: Not at all. You’ll have to tell me, if you read the book. The surprise really was his kindness. He said a thing I find really beautiful, that I put on the back of the book. I think this was his main principle; it’s one of the last things he says. It had to do with finding a way to be kinder to yourself—in a forceful way that would come from being kinder to other people.

“There’s a kind of queer dissatisfaction or emptiness at the core of the self that is unassuageable by outside stuff. And my guess is that that’s been what’s going on, ever since people were hitting each other over the head with clubs. Though describable in a number of different words and cultural argots. And that our particular challenge is that there’s never been more and better stuff coming from the outside, that seems temporarily to sort of fill the hole or drown out the hole.â€

I asked whether internal means could fill it too.

“Personally, I believe that if it’s assuageable in any way it’s by internal means. I think those internal means have to be earned and developed, and it has something to do with, um, the pop-psych phrase is loving yourself. It’s more like, if you can think of times in your life that you’ve treated people with extraordinary decency and love, and pure uninterested concern, just because they were valuable as human beings. The ability to do that with ourselves. To treat ourselves the way we would treat a really good, precious friend. Or a tiny child of ours that we absolutely loved more than life itself. And I think it’s probably possible to achieve that. I think part of the job we’re here for is to learn how to do it. I know that sounds a little pious.â€

Scott Handy: I would like to know what brand of dip DFW dipped. Seriously… Somehow I had him pegged as a Kodiak guy.

David Lipsky: Kodiak. Absolutely. It’s what he brought with him, it’s also what Hal chews (“I really need to quit, it makes your fucking jaw fall offâ€). I double-checked with his family, who say, “Kodiak.â€

I’d just like to thank Matt Bucher and everyone who contributes to wallace-l. I’ve learned a tremendous amount by being one of the serv’s lurkers. When I met Matt at the Footnotes Conference, I was meeting a celebrity.